As inflation, gas prices and other rising costs have strained people’s wallets, housing has continued to be a challenge for buyers and renters alike.

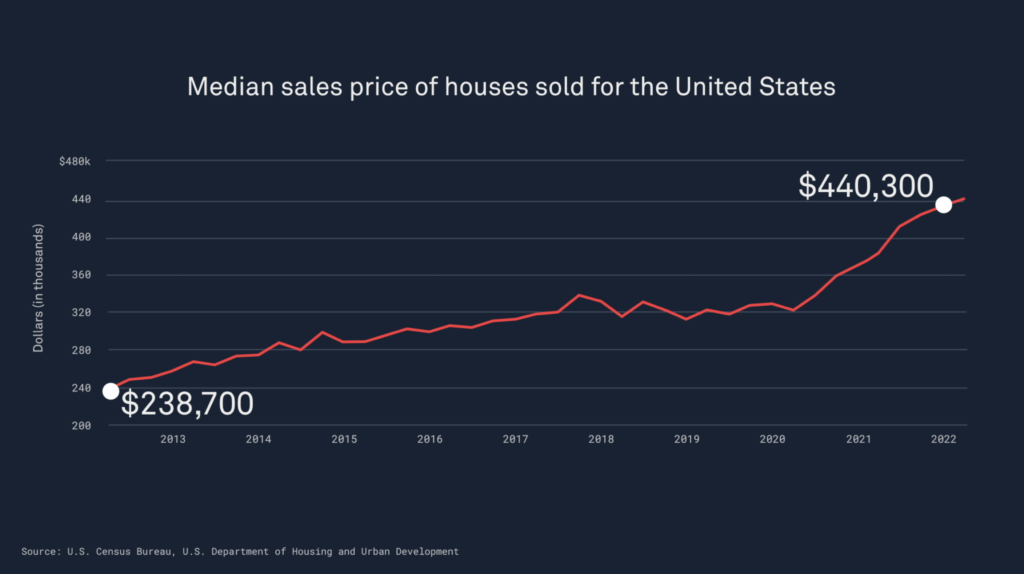

In the past year, the median home price has jumped more than 15 percent, according to data compiled from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. And renters are feeling similar pain: On average, rents in May were up 15 percent than a year before, according to Redfin, but in some cities, like Austin, Nashville, or Seattle, the rise was more than double that.

All of this is making finding and affording shelter increasingly difficult. And while it seems this has been exacerbated in recent months, housing prices have been steadily rising for a decade, pushing homeownership and affordable rentals out of reach for many.

Here’s a look at some of the factors contributing to the difficult housing market, and who is most affected.

Inflation and mortgage rates

In the first quarter of 2021, the median home price in the United States was $369,800, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve. By the first quarter of 2022, the median home price had jumped to $423,600.

Graphic by Jenna Cohen / PBS NewsHour

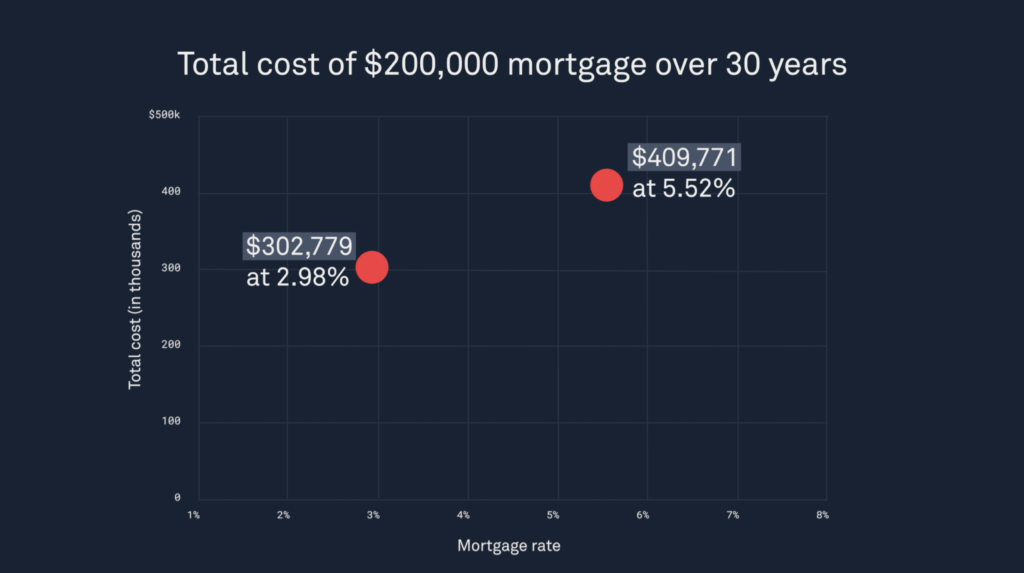

As inflation rose — with the consumer price index hitting a 9 percent year-over-year increase in June, the highest in more than 40 years — the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates. This has led to higher mortgage rates, which are a product of inflation and interest rates, said Daryl Fairweather, chief economist for the real-estate brokerage Redfin. “As inflation has been increasing, it means that anybody who’s lending money knows that they’re not going to really get the true value back unless they charge a higher [mortgage] rate because the money in the future is not going to be worth as much as money today when you have inflation.”

The result has been stark, and pricey, increases. According to Freddie Mac, the average rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage has nearly doubled since this time last year, jumping from 2.8 percent in June of 2021 to 5.52 percent in June of this year.

This has slightly cooled demand for homes and, in turn, home prices. But what people may save in purchase price could be erased when factoring in mortgage rates, which at their current level could add close to $100,000 to the cost of a $200,000 mortgage over the course of 30 years.

Wages

While inflation is a recent factor, home prices have been rising since the bottom of the 2012 housing crash.

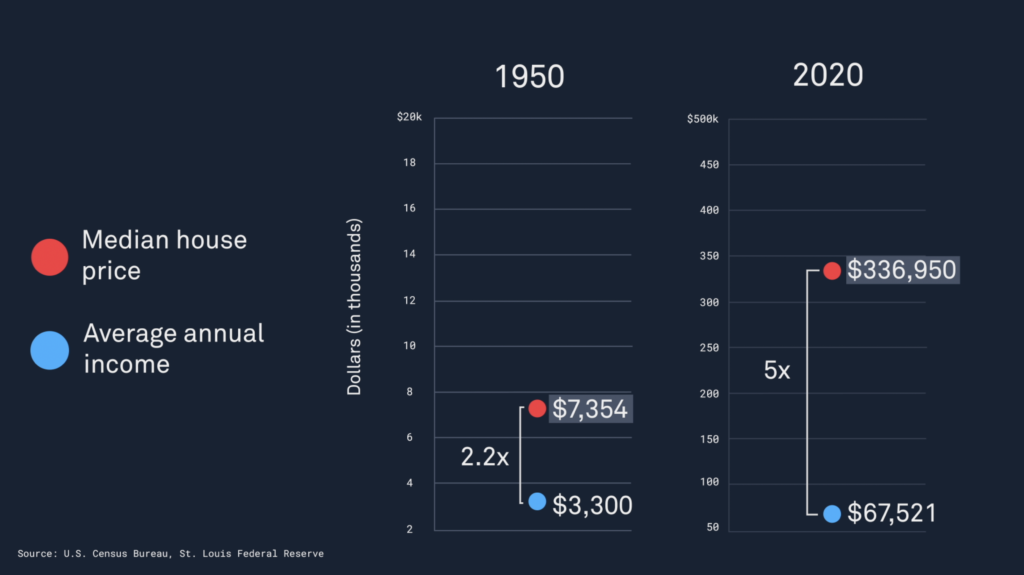

Purchasing a home is out of reach for many people whose wages haven’t kept up with inflation and the general rise in prices. A February 2022 National Association of Realtors report found, a household earning between $75,000 and $100,000 per year could afford about half of active home listings.

In 2020, the median household income level was $67,521, according to Census data analyzed by the Federal Reserve. For people in that income bracket, options diminished quickly — they could afford only 34 percent of available housing stock. Only “35% of White, 25% of Hispanic and only 20% of Black Americans have incomes higher than $100,000,” according to the report.

Amid the skyrocketing prices, many would-be home buyers are essentially left with two options: rent where they are or move elsewhere.

Buying a house in a more affordable area may seem appealing, but could be untenable for those who need to live where they work. And, buying a home in a different market creates its own ripple effects.

Graphic by Jenna Cohen / PBS NewsHour

If a prospective homebuyer lives in San Francisco, “where the median home price is $1.5 million, and you move to Sacramento where it’s more like $450,000, that’s a huge savings,” Fairweather said. “But what happens then is that home prices in Sacramento go up and the people who are living in Sacramento renting, for example, they face a lot more competition. Their property taxes, probably taxes go up, too. And so locals get priced out and they have to then again move to the next most affordable metro.”

Even smaller apartments are too expensive for lower-income workers, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. In 2021, a worker would need to earn $24.90 per hour to afford a “modest two bedroom apartment,” NLIHC wrote in a recent report While some states and cities have minimum wages higher than the federal minimum of $7.25 per hour, no worker anywhere in the country earning a state, federal or local minimum wage for a 40-hour work week can currently afford “a modest two-bedroom rental home at fair market rent, the report said.

“The housing at the low end of the rental market,” said Steve Berg, Vice President of Programs and Policy at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, “has continually gone up substantially faster than earnings at the lower end of the wage market.”

The largest issue in the cost of finding shelter is supply. According to Freddie Mac, the United States has a deficit of 3.8 million units needed to meet current demand.

“Builders have not built enough to meet demand,” Fairweather said. “We had fewer homes built in the 2010’s than any decade going back over the 1960s. But the net demand has continued to increase, especially as millennials have entered into home buying age.”

Graphic by Jenna Cohen / PBS NewsHour

Washington, D.C., for instance, was about 156,000 units short of what it needed in 2019, according to a new report Up For Growth, a nonprofit devoted to ending the housing shortage. And over the last decade, Phoenix, Boise and Salt Lake City fell 5 percent of what they needed that year, the report said.

“Somebody compared it to a game of musical chairs, you know, you’re left out,” Berg said. “They’re not getting left out because they’re a slow runner. They’re getting left out because there’s not enough chairs.

While federal rental assistance is available, primarily through the Housing Choice Voucher program, the program can’t provide help to everyone that needs it, Berg said. Under the program,the federal government pays some or all of the rent for low-income families, people with disabilities and the elderly.

“It’s funded so that about a quarter of the people who need help actually get the help. And the other three quarters go on a waiting list and sometimes wait for years to get in the program,”Berg said.

Zoned out

The best solution, Berg said, is for communities to build modest rental housing. But local zoning laws can pose significant barriers to that happening. “There’s a phenomenon called NIMBYism, not in my backyard, where people who have already bought a home, a single family home, oftentimes don’t want their neighborhood to change”with the addition of smaller, more affordable homes, Fairweather said.

When zoning constricts new higher-density construction, that can drive up home prices and rent prices, and prices some people out of housing entirely. A 2020 Government Accountability Office study found that with all other things being equal, a $100 dollar increase in the median rent was associated with a 9 percent increase in the estimated homelessness rate in the U.S.

The big picture

Housing in America has typically been used as way to build wealth. But in a housing crisis where some can’t find a home within their means or at all, there are generational financial and socio-economic consequences, too, experts say.

“If housing is the primary source of wealth and it’s passed down from generation to generation, then it really matters whether or not your grandparents were in a position to buy a home back in, say, like the 1950s or sixties before the Civil Rights Act was passed,” Fairweather said.

These consequences for generational wealth can also exacerbate the racial wealth gap, a 2021 Brookings study notes.

“Homeownership is often viewed as the entree to the American dream and the gateway to intergenerational wealth. However, this pathway is often less achievable for Black Americans who post a homeownership rate of 46.4% compared to 75.8% of white families,” the study notes. “Homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods across the country are valued at $48,000 less than predominantly white neighborhoods for a cumulative loss in equity of approximately $156 billion. These are significant contributing factors to the racial wealth gap.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eelsGqu81obGaqlZbAsLrSZp%2BoraOeu6h5yKxkrKddmsWxsc2soK%2BdXae2qLTTZqWorw%3D%3D